This site uses only a few technical cookies necessary for its operation. By continuing to browse, you accept their use.

To find out more...

To find out more...

The (small) miracle of béchamel sauce

Making a béchamel sauce is going to confront you with a little miracle that happens every time: You pour milk over a roux, it's very liquid, you stir over a low heat, and then all of a sudden, miracle, the sauce sets, it thickens, you've got your béchamel.

Let's see what happened.

Let's see what happened.

8,954 4/5 (4 reviews)

Keywords for this post:SauceMethodPrincipleExplanationStarchTemperatureRouxConsistencyBéchamelLast modified on: August 27th 2024

The (small) miracle of béchamel sauce

A basic sauce

Making it is quite simple: first a "roux" mixture of flour and butter, which is heated and colored (hence its name).

Once the roux has reached the right color, cold milk is added, the mixture is very liquid, and you continue to cook and stir over low heat until it thickens (you'll find the full recipe here).

But why does it thicken? As you'd expect, there's no magic involved, just a little physics and chemistry.

Flour and starch

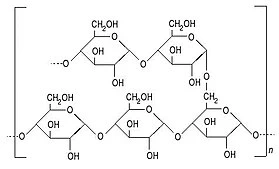

The secret lies in the roux's flour, which contains grains of starch, a complex sugar made up of glucose molecules rolled up into tiny little balls.

It's around 70°C that the magic happens: the grains of starch in the flour break up into smaller grains, starch molecules that begin to absorb the milk around them, up to 20 times their volume, thus increasing the sauce's viscosity.

This process, known as starch gelatinization, takes place between 70°C and 85°C, giving béchamel its characteristic thick, creamy consistency.

Note in passing that this process of starch gelatinization is also at work in, among other things, crème pâtissière or flan, where flour is often replaced by maïzena, a corn starch.

In short: Béchamel thickens because it contains flour that is heated, causing its starch grains to burst and absorb the milk around them.

So béchamel is not just a culinary classic, it's also a little chemistry lesson in action.

Lasts posts

XO Cognac Explained: Meaning, Aging, and Flavor Profile

XO Cognac always goes beyond the labels on the bottle: it is often associated with tradition and quality. You get to appreciate the artistry, character and ageing process when you understand what defines this smooth Cognac. The section below tackles everything about XO Cognac, from complex flavour...January 28th 2026684 Sponsored article

Butter vs. grease

We often read in a recipe where a pastry is put into a mould that, just before pouring, the mould should be buttered or greased. But what's the difference between these 2 terms?December 1st 20252,4965

Getting out of the fridge early

Very often when you're cooking, you need to take food or preparations out of the fridge, to use them in the recipe in progress. There's nothing tricky about this: you just take them out of the fridge and use them, usually immediately, in the recipe. But is this really a good method?November 24th 20251,6335

Who's making the croissants?

When you look at a bakery from the outside, you naturally think that in the bakery, the bakers make the bread, and in the laboratory, the pastry chefs make the cakes. It's very often like that, with each of these professions having quite different ways of working, but sometimes there's also one...November 23th 20251,476

Oven height

When we put a dish or cake in the oven, we naturally tend to put it on the middle shelf, and that's what we usually do. But in some cases, this position and height can be a little tricky, so let's find out why.October 8th 20254,8455

Other pages you may also like

Making the most of seeds: Dry roasting

In cooking, and particularly in baking, there are a lot of seeds we can use, such as linseed, sesame, poppy, etc. Usually, recipes simply say to add them just as they are to the mixture or dough. To make a seeded loaf, for example, prepare a plain bread dough as usual, then, towards the end of...January 30th 201563 K4.0

Preserving egg yolks

If you're using only the egg whites in a recipe (such as meringues ), you'll need to store the yolks until you're ready to use them again. There's nothing very complicated about this in principle - all you have to do is chill them, but there are a few pitfalls to be avoided in practice.June 18th 20248,6075

What is the difference between bakery and patisserie?

This is a question that you may well have asked yourself and which I will attempt to answer. In France the two trades of "boulangerie" (bakery) and "pâtisserie" (patisserie and confectionery) have always been quite distinct, but where exactly do the boundaries lie? .February 7th 2017135 K 14.1

The 3 kinds of meringue

Meringue – what could be simpler? Just beaten egg whites with sugar added. This makes a fairly stiff mixture which can then be cooked in a cool oven to create those lovely, light confections. But in the world of professional patisserie, meringue comes in three different kinds. Even if the...June 14th 201365 K4.5

Candied fruits: don't get ripped off

Do you like candied fruit? You might like to nibble a handful or add it to a recipe, like a classic fruit cake or delicious Italian specialities like panettone or sicilian epiphany pie.June 21th 201769 K 24.2

Post a comment or question

Follow this page

If you are interested in this page, you can "follow" it, by entering your email address here. You will then receive a notification immediately each time the page is modified or a new comment is added. Please note that you will need to confirm this following.

Note: We'll never share your e-mail address with anyone else.

Alternatively: you can subscribe to the mailing list of cooling-ez.com , you will receive a e-mail for each new recipe published on the site.